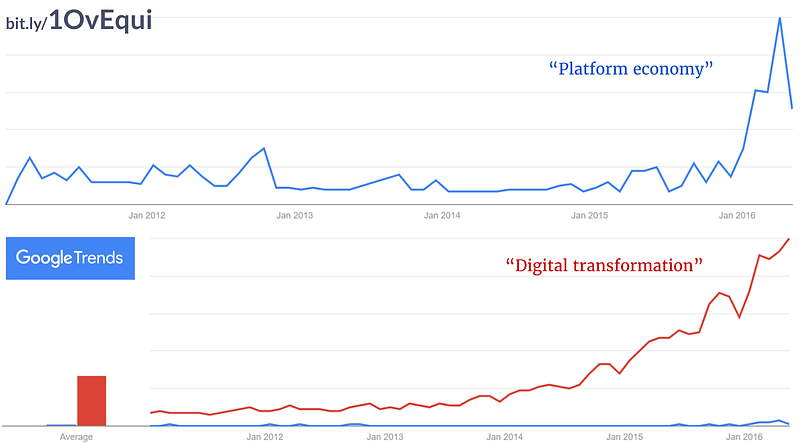

The Platform Economy Hype

Had you asked me as little as two or three months ago what was meant by the platform economy, I would have pointed to the darlings of the cloud world — Salesforce, Amazon’s AWS and Microsoft’s Azure. These, to me as a techy, were platforms — services on which other applications and products were built on.

But since the end of 2015, a new wave of hype has been created around ‘the platform economy’ which, like most techy hype waves, just serves to confuse people. Grandiose statements about this new, bleeding edge technology become widespread.

“By embracing the transformational power of platforms, enterprises across all industries are capturing new growth opportunities and changing the way they do business” — Accenture

Not only is this transformational power going to disrupt the world as we know it, but similarly everyone (other than you) already seems to have leapt on the bandwagon, picked up an instrument and committed firmly to the melody.

“81% of executives say platform-based business models will be core to their growth strategy within three years.” — also Accenture.

Other similarly terrifying facts follow. Accenture claim that the top 15 public ‘platform companies’ have a market capitalisation of $2.6 trillion. The Center for Global Enterprise claim that the market cap of the global players is $4.3 trillion. Clearly, if you don’t have a platform company, you’re doing something wrong.

What makes a platform?

In Fez, Morocco, squats the Chouara tannery, the largest of three local tanneries that supply the leather industry at the local souks. Visitors to Chouara, which was first built in the 11th century, are greeted with sprigs of mint. These aren’t thoughtful mementos, but rather to hold under your nose to ward off the stench of the quicklime, pigeon droppings and cow urine which is used in various stages of the production process.

But this tannery allows us to see a glimpse of one of the earliest platforms. Hides are brought to the tanners, who pass them to fleshers, and then on to leather workers and finally to the market where the goods are sold. The tannery itself exists as a monument to the importance of drawing a crowd, and co-locating the means of value addition through the supply chain.

Other marketplaces of course exist. The Amsterdam Stock Exchange, considered the first of its kind in the world, was built in 1602 and was defined by “the volume, the fluidity of the market and publicity it received, and the speculative freedom of transactions”. That definition of the Amsterdam Bourse could equally be applied to eBay, arguably the first of the digital platform companies, created a not inconsiderable 21 years ago.

The Digital Platform Economy

So, what then is the digital platform economy? What defines the companies that, as Accenture’s report claims are “developing power that may be even more formidable than was that of the factory owners in the early industrial revolution”?

First, we can look at the companies that have had the term applied to them. Certainly eBay, Salesforce and Facebook fit the brief, but this new platform wave also includes unicorn darlings like Uber, Lyft and Square. In the past, other terms would almost certainly have been used to define these businesses; ebay is a classifieds site, Salesforce a Software-as-a-Service (Saas) business, Facebook and LinkedIn were social networks. These were the old guard of other waves — Web 2.0 and the post-dotcom-boom boom.

But platform is the new word that not only defines these businesses, but also adds to the bubble of their valuation. Ev Williams, latterly of Twitter and now of Medium, has described Medium itself as a platform not a publishing tool. The cheerleaders for this new platform boom are, of course Uber and AirBnB, and it’s their business models that have driven the interest in the ‘sharing economy’, an almost untested experiment in unlocking the value of personal assets (especially time), which many believe can deliver significant social good by diverting funds from massive corporations, and into the pockets of Joe and Joanne Public.

Defining the Platform

What then are the key traits of platform companies? The problem in answering this question is that the application of the term ‘platform’ is so diverse, a marketing term liberally applied to make companies sparkle.

The Centre for Global Enterprise have decided that “a platform business can be defined as a medium which lets others connect to it”. But while this is short and pithy, I find it hard to apply; the platform economy is too malformed to have this razor of definition applied to it.

In coming up with my own definition, I found that there were three traits exhibited by the companies that most apparently represented this generation of the platform economy. By looking for these traits, squint and you might be able to pick a platform company in a line up.

Trait No. 1 — Bilateral Markets

In almost every case, digital platforms require two (or many) sided markets. Uber introduces riders and drivers, eBay buyers to sellers, and LinkedIn recruiters to job seekers. In some more esoteric multilateral models like YouTube, the platforms match viewers with advertisers and content producers.

But in all of these models, the platforms themselves produce very little except a match. The service they provide to the consumers of that match may be complex — like the logistics and routing platform of Uber, the payments of Paypal, or the social proofing of AirBnB — but the match is the crux of the platform.

As the platform economy grows, the types of audience matches are becoming increasingly niche, with platforms delivering food locally like Deliveroo, or laundry services like Laundrapp. We’ll no doubt see both a proliferation of these micro-niches as startups rush to fill them, and a platform scale-up play, as giants like Amazon add market after market to their platform.

Trait No. 2 — Network Effect

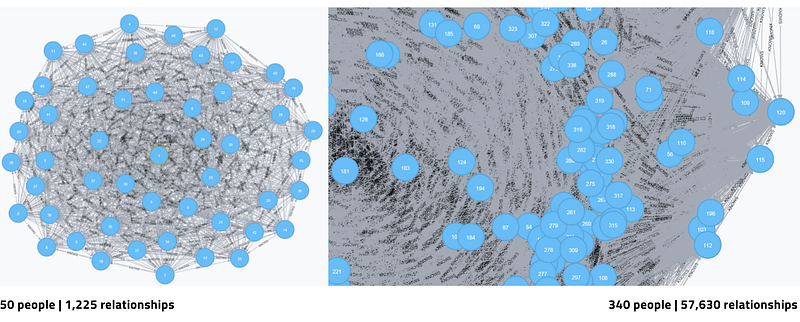

Metcalfe’s law states that the value of a telecommunications network is proportional to the square of the number of connected users of the system. This law was liberally invoked to explain the power of Facebook and Twitter in the last era of social networks, but the same law is critical to the success of platform companies.

Platforms, by virtue of their position brokering matches between agents in the market, tend to have very low margins and therefore can only become profitable by achieving significant scale. This scale relies heavily on the power of the network effects, as it increases the number of relationships within the platform at a non-linear rate. For both the consumer and the supplier served by the platform, the attractiveness of the service grows primarily with the number of available relationships.

Trait No. 3 — Technology First

It almost goes without saying that this generation of digital platforms are marked by their use of technology. Banks, credit card issuers, stock exchanges and even cattle markets meet both other criteria for platform companies, but our digital platforms rely on technology for a number of critical reasons, the first of which is in sustaining the growth of the network at affordable levels.

It’s perhaps ironic that this new generation of platform companies relies almost entirely on the existence of their platform forebears. The ‘hyperscale’ clouds — Microsoft’s Azure, Amazon AWS and Google Cloud Platform — will almost invariably be the technology supplier of choice for new platform startups. Not only is the technology cheaper to acquire than ever before, but the elasticity and friction-free scaling of the clouds is what allows poorly funded startups to enter and test markets. Startups are able to host their platforms and scale their services more cheaply as the cost of compute, storage and connectivity falls.

But consumer technology also has a part to play in the growth of these platforms. With near-ubiquitous internet connections and ever-present mobile devices, consumers can always connect to their chosen platform. There would be no Uber without iOS and Android, and no Netflix without broadband.

Building your own platform strategy

If you’re still feeling that you’re missing a fast moving boat, fret not. Whatever your own industry, you can consider how relevant the traits of these platforms are to your current business model. Do you currently have access to a large audience or strong brand? Are you in a position to broker a match between two sides of a market? Would it be attractive to you to switch to a high transaction/low margin model? Do you have the technical capability to develop a platform, or would you need to bring in resource from outside the business?

There are two other lessons to be learned from other players in the platform world. If you consider building your own platform, you should ensure that you test and dominate a highly specific market first. For Facebook this was famously Harvard students; for Yelp it was business reviews in San Francisco and for Deliveroo it was food deliveries in the posher parts of West London. Platforms do require scale, but layers of scale can be added thanks to the elasticity of the technology they use.

The second lesson for new platforms is to sign up anchor clients — those critical brands that will ensure that your audience will not only want to use you, but will also infuse credibility into your service. Deliveroo ensured that they found the most popular local restaurants and signed them up, but also brought on the Jamie Oliver megabrand with unique lunch options, giving their audience access to something other food delivery platforms couldn’t. For the streaming platforms like Netflix it was a deliberate strategy to commission unique and high quality content like the Kevin Spacey triumph, House of Cards.

Don’t rush to build a platform

With all this talk of platforms it’s easy to think that you’re getting left behind, but the truth is that they are just one of many workable business models — not every business feels comfortable with technology investment, or high volume, low margin transactions. There’s nothing in the Big Book of Business that says that you must rush to copy this model, either.

It’s also worth noting that the platform darlings are not risk averse. In the case of AirBnB and Uber, their new brokerage models have directly challenged legislation that has been in place for decades to regulate the hospitality and private hire industries. If your business is uncomfortable challenging well established laws and norms — perhaps to protect your brand and reputation — a platform may not be a suitable model for you.

In the long term, platform players appear to need to dominate their market to be profitable. The scale is not just addictive, but necessary. AirBnB and Uber, both now 7 years old, will likely not break even until around 2020. In AirBnB’s case, this will be on a projected $10bn of revenue. These are long range plays, though; Apple and Google (who have hybrid platforms courtesy of the App Store and Google’s search model) show some of the highest profits per employee of any company in the world. We’re watching with interest to see if this new generation can even come close to their performance.

Perhaps the real money will be made from this particular gold rush when a platform emerges to let other companies build their own platform; a platform platform if you will. This would be that most inspired of business models, not digging for gold but selling shovels.