Every so often I sit down to write an article, taking some time to imagine how today’s magical technology might unfurl into one of many possible near-futures. In part, this a challenge to think creatively about the application of technology. In equal part though, it’s so I can look back in five years and laugh at how wrong I was.

In my last imaginary excursion, I considered what the future of autonomous vehicles might mean for us as consumers of transportation, and how robot cars would impact the massive workforces in related industries. Today, I’d like to consider “The shop of the future”.

The shop of the future

Even today, shopping already exists in a form that a time-traveller from the neon 1980s would struggle to understand. The merchant in the bazaar may be one of the oldest human interactions but has irrevocably changed in only the last 15 years. The changes wrought by Amazon to the ease of retail consumption, or by the Apple Store to our expectations of in-store shopper experience, have changed our consumer expectations of the traditional shopping experience beyond measure. Even the mighty bastions of retail, the ancient and storied department stores of New York’s Fifth Avenue, are falling prey to a new generation of occupants, as co-working offices displace retail outlets in the world’s most expensive shopping streets.

Discovery & Delivery

Of course, the key driver for this change is the arrival of the internet. The way we discover products has changed, but it is the near-immediate, same day gratification that is the largest driver of a shopping culture unrecognizable to our 1980s tourist. An internet lifetime (or about two earth years) ago, Amazon’s Prime Now delivery service was recording delivery times from checkout to letterbox in under 20 minutes in London, one of the most congested cities in the world.

Many of us who are still, remarkably, alive can remember a time of a weekly grocery shop, and where the purchase of a specialist item – a stereo or a particularly fancy brand of shoes – meant planning a trip to a distant town where the elusive and magical shopping nirvana existed.

But this change isn’t even close to being done. Of course, shopping of the future will have drone deliveries — everyone knows that. Advances in artificial intelligence and computer recognition mean that Amazon’s aerial delivery drones will be joined by Pizza Hut’s in a battle for the sky, while Just Eat’s foodbots will scurry around at ground level (they’ve already made over 1000 deliveries in London).

But this isn’t being farsighted enough. Sure, 30 minutes for the drone to arrive is quick. But we can go further; the growth in popularity and complexity of 3D printing means that we can already download blueprints and print items at home. Imagine how this escalates — five years from now today’s niche for early adopters, printing novelty trinkets, becomes your regular visit to Amazon. Popping something into your basket grants you the digital rights to the item. Just as MP3s replaced vinyl, digital plans replace physical stock in retailer warehouses. Instead of cardboard boxes with smiley A-Z faces, your delivery will be the wait time for your Makerbot to print your item. Meanwhile, your regular weekly shop will be a throwback to coal deliveries, with vats of raw materials needed to print the most common items — metals, plastics and maybe even food — stored in bunkers outside your back door.

And this, like so many other wonderful, impossible technologies is not only imminent, but only a blink away from science fiction. Remember the Star Trek replicator, a device that immediately created anything you could ask for? Current 3D printers are different only in resolution, and that resolution is already starting to show hints of high definition. In 2015, University of Illinois chemist, Martin Burke, created a machine which can effectively print chemicals (even those which have never been previously synthesised) at a molecular level. While years from being useful outside of biochemistry and drug design, Burke’s work hints at a future not unlike Roddenberry’s Star Trek dreams.

Discovery and Marketing

In 1886, Richard Warren Sears, a railway agent in Minnesota received a delivery of unwanted watches. Seizing the initiative, Sears sold the watches and discovered an untapped retail market, realizing that he could increase sales by offering watches through mail order, forever changing the paradigm of face to face shopping. Joined shortly after by Alva Roebuck, the pair diversified their offer for time-poor farmers. By 1894 their catalogue was 322 pages. By 1897, you could buy ear trumpets, horse buggies and opium, the 19th century predecessor to eBay.

Just as Sears and Roebuck’s revolution in the 19th Century mimics our own 21st century wonder, there is a similar pattern repeating: the birth and rebirth of advertising.

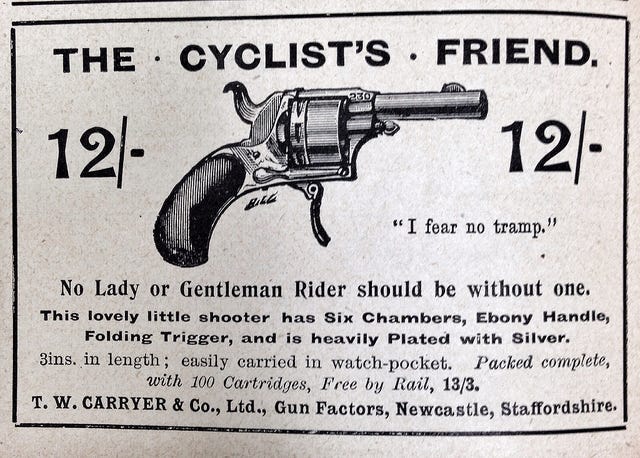

In the days of the Sears & Roebuck catalogue, discovery of brands was controlled more through the channel of sale than through brand advertising. In early 19th century America, most advertising was by local merchants selling to their own communities, leading with the commodity rather than the brand. In the UK, advertising was experiencing a tumultuous period, weaving from bill posting to newspaper ads.

It was the growth of mass transport in both the US and the UK that drove advertising into the mainstream. As the industrial revolution drove economies of scale, companies started to clamour for an audience outside of their own neighbourhoods. In post-Civil War America, companies became brands, and brands demanded advertising.

Since then, advertising has seen the birth of branded packaging and radio, Television and the soap opera. In our internet age, we’ve added banner adverts, page takeovers and YouTube pre-rolls.

In the magical old days, our buying habits for items were controlled through relatively narrow channels: the supermarket, two channels of TV advertising, radio and outdoor posters. Brands, from the times of soap advertising and Mad Men needed strong visuals, compelling creatives and memorable jingles because we needed to choose the products as we passed them in the aisle. The supermarket, grocery or pharmacy was the gateway to the world of fast moving consumer goods, sometimes leading us to a particular product with free samples or dog eared coupons cut out of a daily newspaper.

What’s interesting about these products is the psychology behind the shopper choice. I recall, as a freshly minted student on my first solo grocery shop, selecting the brands that I’d grown up with. They were familiar – the colours and logos were comforting, the smells of soap and washing powder reminded me of home. And so, my habits formed because of the physicality of the shopping experience, of pushing a trolley through an overcrowded supermarket.

But this physicality is increasingly waning, as these weekly necessities are delivered by a van, in neatly sorted bags. This threatens the value of the packaging, and maybe even (big-B) Brand itself. Amazon has been successfully selling the brown-box ‘Amazon Basics’ alternatives for years, but this year quietly launched a number of their own fashion brands, whilst simultaneously launching new, in-home services that will help dress you. Increasingly, Amazon — perhaps more so than Google and Facebook — becomes the primary medium to control buyer choice, just like those dusty gold-rush stores selling shovels in California.

But I doubt physical goods will give up without a fight. Perhaps in more traditional stores, we’ll see technology take the fight to the shelves with electronic ink and the ‘internet of things’ finding its way into packaging. We’ve heard about A/B testing on websites, where two versions of a design are shown to different groups of consumers to judge which is more effective. Digital packaging might allow brands to choose designs and colours that are updated not on every few months, but while it’s stacked on the shelf to reflect the latest, and most effective version of a design. Let’s take a braver leap; maybe that same packaging will contain sensors that are aware of their surroundings and change, like chameleons or octopuses, to have the most flamboyant and effective markings, one toothpaste dispenser desperately trying to out-compete a mouthwash on the next shelf like digital peacocks.

Personalisation

Early this year, Adidas returned some of it’s manufacturing capacity to Germany, with the creation of its new ‘Speedfactory’. These ultra-modern factories are heavily robotised, utilising 3D printing and other modern rapid production methods, threatening the economic benefits of production in Asia. They bring not just the opportunity to cut delivery costs by creating products within a local market but also the promise of product micro-personalisation.

If the factories are able to craft unique variations in products, imagine how this can tie into the growth of ubiquitous retailer awareness. The Amazon Echo Look, which can take photos of you as you stand in your bedroom today, could be enhanced with iPhone X style depth-awareness. Standing in front of Alexa, you prepare to be scanned and sampled, your dimensions stored and processed, fed to a garment factory which produces unique, perfectly tailored, bespoke fashion which fits you every time. No more S, M or L. No wrong sizes, no returns. Perhaps no privacy, but that’s a small price to pay for a snug first time fit, no?

Now it’s your turn

What then does the future look like? Immersive, virtual environments, serving you perfect representations of 50s film icons (wearing Adidas trainers) while you sit in your autonomous car? Molecular printed fashion, tailored to the millimeter to fit your laser-scanned curves? Organic food, designer earth still clinging artistically to it, hand delivered by real artisan farmers, or nutritionally perfect soup designed by scientists to taste of synthetic rainbows?

I don’t know, but it’s sure going to be fun finding out.